Have you ever accidently missed a red light or a stop sign? Or have you heard someone mention a visible event that you passed by but totally missed seeing?

“When we have different things competing for our attention, we can only be aware of so much of what we see,” said Kyle Mathewson, Beckman Institute Postdoctoral Fellow. “For example, when you’re driving, you might really be concentrating on obeying traffic signals.”

But say there’s an unexpected event: an emergency vehicle, a pedestrian, or an animal running into the road—will you actually see the unexpected, or will you be so focused on your initial task that you don’t notice?

“In the car, we may see something so brief or so faint, while we’re paying attention to something else, that the event won’t come into our awareness,” says Mathewson. “If you present this scenario hundreds of times to someone, sometimes they will see the unexpected event, and sometimes they won’t because their brain is in a different preparation state.”

The researchers used both electroencephalography (EEG) and the event-related optical signal (EROS), developed in the Cognitive Neuroimaging Laboratory of Gabriele Gratton and Monica Fabiani, professors of psychology and members of the Beckman Institute’s Cognitive Neuroscience Group, and authors of the study.

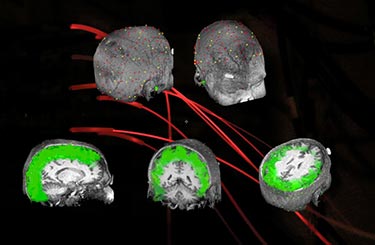

While EEG records the electrical activity along the scalp, EROS uses infrared light passed through optical fibers to measure changes in optical properties in the active areas of the cerebral cortex. Because of the hard skull between the EEG sensors and the brain, it can be difficult to find exactly WHERE signals are produced. EROS, which examines how light is scattered, can noninvasively pinpoint activity within the brain.

“EROS is based on near-infrared light,” explained Fabiani and Gratton via email. “It exploits the fact that when neurons are active, they swell a little, becoming slightly more transparent to light: this allows us to determine when a particular part of the cortex is processing information, as well as where the activity occurs.”

This allowed the researchers to not only measure activity in the brain, but also allowed them to map where the alpha oscillations were originating. Their discovery: the alpha waves are produced in the cuneus, located in the part of the brain that processes visual information.

The alpha can inhibit what is processed visually, making it hard for you to see something unexpected.

By focusing your attention and concentrating more fully on what you are experiencing, however, the executive function of the brain can come into play and provide “top-down” control—putting a brake on the alpha waves, thus allowing you to see things that you might have missed in a more relaxed state.

“We found that the same brain regions known to control our attention are involved in suppressing the alpha waves and improving our ability to detect hard-to-see targets,” said Diane Beck, a member of the Beckman's Cognitive Neuroscience Group, and one of the study’s authors.

“Knowing where the waves originate means we can target that area specifically with electrical stimulation” said Mathewson. “Or we can also give people moment-to-moment feedback, which could be used to alert drivers that they are not paying attention and should increase their focus on the road ahead, or in other situations alert students in a classroom that they need to focus more, or athletes, or pilots and equipment operators.”

The study examined 16 subjects and mapped the electrical and optical data onto individual MRI brain images.

Other researchers on the study include Ed Maclin and Kathy Low, from the Cognitive Neuroimaging Lab, and Tony Ro, from the City College of the City University of New York. Funding was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Beckman Institute, and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).